By Susan Stopper

What is the right amount of daily homework for a third grader? How about none.

That’s the viewpoint at The School in Rose Valley (SRV) outside Media, PA.

For years, schools have relied on homework, grades, worksheets and tests to educate and evaluate students. But research indicates these tools may do more harm than good. SRV takes a different approach — no standardized tests, no traditional grades and no daily homework.

Intrinsic Motivation

“We are trying to build intrinsic motivation rather than relying on a system of external punishment and rewards,” says Rod Stanton, head of school at SRV, an independent school for children in preschool through sixth grade. “Therefore, standardized tests, traditional grades, daily homework and rewards for learning are absent from the curriculum. Because grades, an extrinsic reward, have been shown to reduce intrinsic motivation, we don’t employ them.”

In place of report cards, teachers at SRV construct a nuanced narrative about each student twice a year to let parents know how their child is doing mastering concepts. Teachers take daily notes on students’ work, conference with students, and communicate regularly with parents about their children’s progress and curriculum.

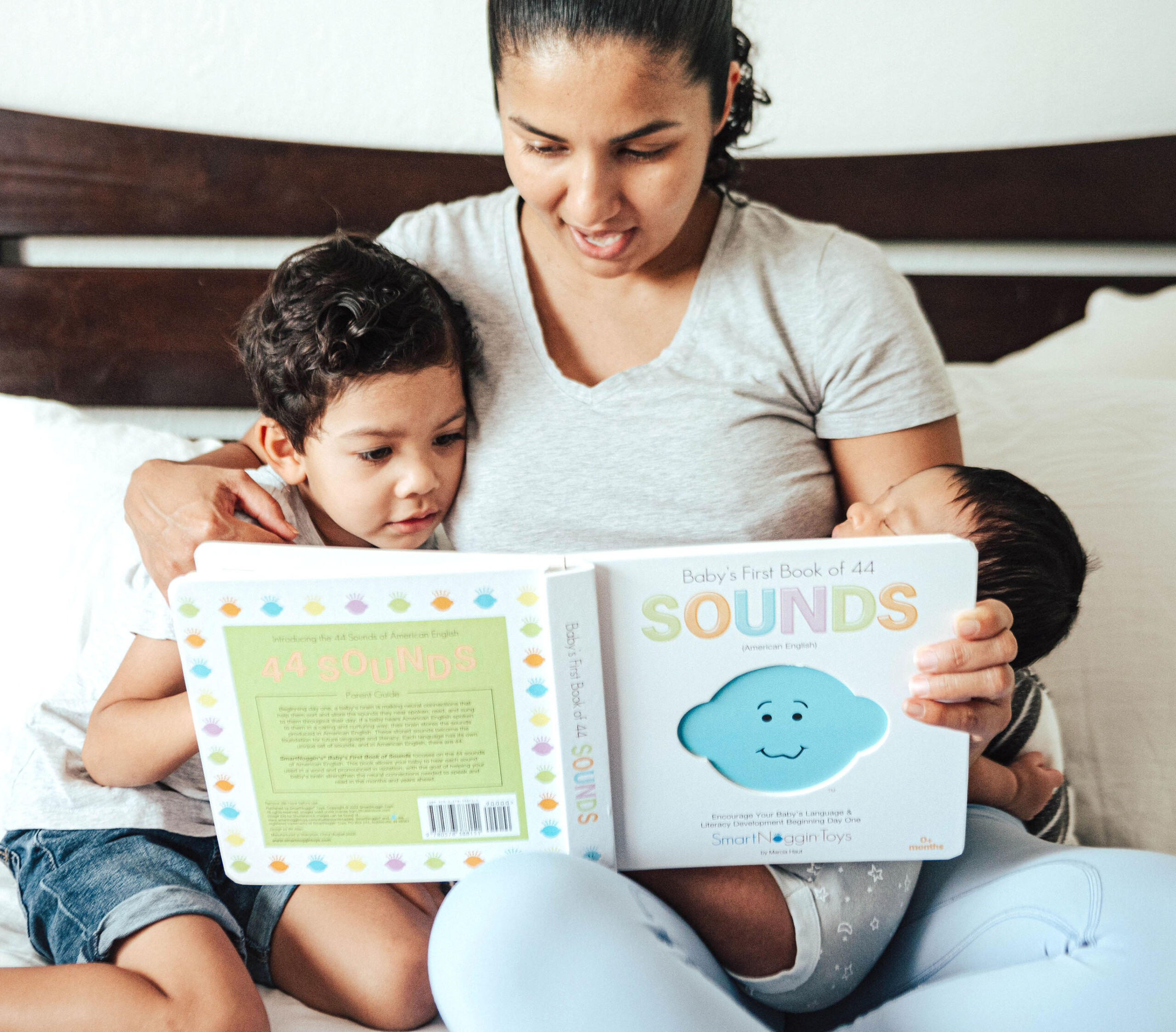

Parents and children are encouraged to read together nightly and older students occasionally receive homework to reinforce concepts, but daily homework is largely absent from the school.

Diane Luckman, third and fourth grade teacher at SRV says, “Because students and teachers are not just worried about a grade, we can spend the time to understand what it means to have an individual student do his or her best. No grades allows me the space and time during the day to conference with individual students and work towards true mastery, rather than teaching to the test.”

“There is absolutely no evidence of any academic benefit from assigning homework in elementary or middle school,” says Stanton. “The negative effects of homework, on the other hand, are monumental.”

Stanton explains that children are often tired at the end of a school day, and homework can add to that exhaustion and eliminate time for extracurricular activities that are beneficial to children’s education and development. Parents often complain that they end up arguing with their children to do homework, causing stress in the family, and many parents worry that they will be criticized for helping too much or not enough. All of that stress can cause children to resent school and lose interest in learning.

Experiential, Student-Centered Learning

At SRV, students don’t spend their time in school glued to their desks completing worksheets either. As part of the school’s progressive approach to education, ample time for free play and indoor and outdoor exploration is built into every day.

“The progressive approach can vary widely from school to school but is traditionally characterized by experiential learning, an integrated curriculum, and democratic values,” explains Stanton. “Research shows that when students are able to spend more time thinking about ideas than memorizing facts and practicing skills — and when they are invited to help direct their own learning — they are not only more likely to enjoy what they’re doing but to do it better.”

Teachers take note of the students’ interests and create a curriculum tailored to the students rather than teaching a pre-packaged curriculum. Without the pressure and constraints of preparing for standardized tests, students and teachers have the freedom and flexibility to dive deeply into a subject and give all learning a context, a meaning and a purpose. For instance, the fifth and sixth grade class built a new sheep house and while doing so, learned and applied multidisciplinary concepts in engineering, math, woodworking and agriculture.

Students work together and help each other in multi-age classrooms, as well as tend to their 9-acre wooded campus and the school’s 18 chickens, two sheep and 3,000-square-foot garden. All of the produce from the garden is incorporated into the school’s lunches. Students support their local community by participating in service-learning projects, such as preserving wildlife, baking for senior citizens and partnering with diverse organizations and schools, such as the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf.

At SRV, Stanton says, “We attend to the whole child. Our students’ physical, social, and emotional development are equally important to their cognitive development.”

After The School at Rose Valley

Most SRV graduates go on to public school after sixth grade. Though life after SRV is different, with grades, homework and less outdoor time, Stanton says their students’ ability to adapt to any environment sets the stage for success. At SRV, they’ve learned to self-advocate, problem solve, think deeply, apply concepts in various settings and, most importantly, develop a love of learning.