Kareem Rosser has already accomplished a lot in his 29 years—but the Philadelphia native’s current goal is to give back to his hometown. His Philly roots run deep.

“I really wanted to tell our story in a way that hadn’t been told before,” says Rosser. “Hopefully, it inspires a few people who are looking for a little inspiration and hope.”

The lights and cameras of major news networks, including ESPN and “60 Minutes,” have faded. They captured the highlights, Rosser says, but not necessarily “the adversity we dealt with as kids, coming where we came from.”

Coming from ‘The Bottom’

Rosser’s childhood neighborhood, “The Bottom,” is known for its poverty and violence. To say it was an unlikely home for the United States Polo Association’s (USPA) High School National Championship team is an understatement. But Philly loves an underdog story.

That 2011 high school championship win, captained by Rosser, made history as the first by an all-Black squad. Rosser led his Colorado State University team to a national championship in 2015 and was named USPA’s Intercollegiate Player of the Year. He’s considered the best African American polo player.

“Polo being a predominantly white sport, I found myself in many places where I was the only Black face or person of color. In the beginning, it was uncomfortable … but over time I just became used to it, and luckily most people were accepting of me,” Rosser says.

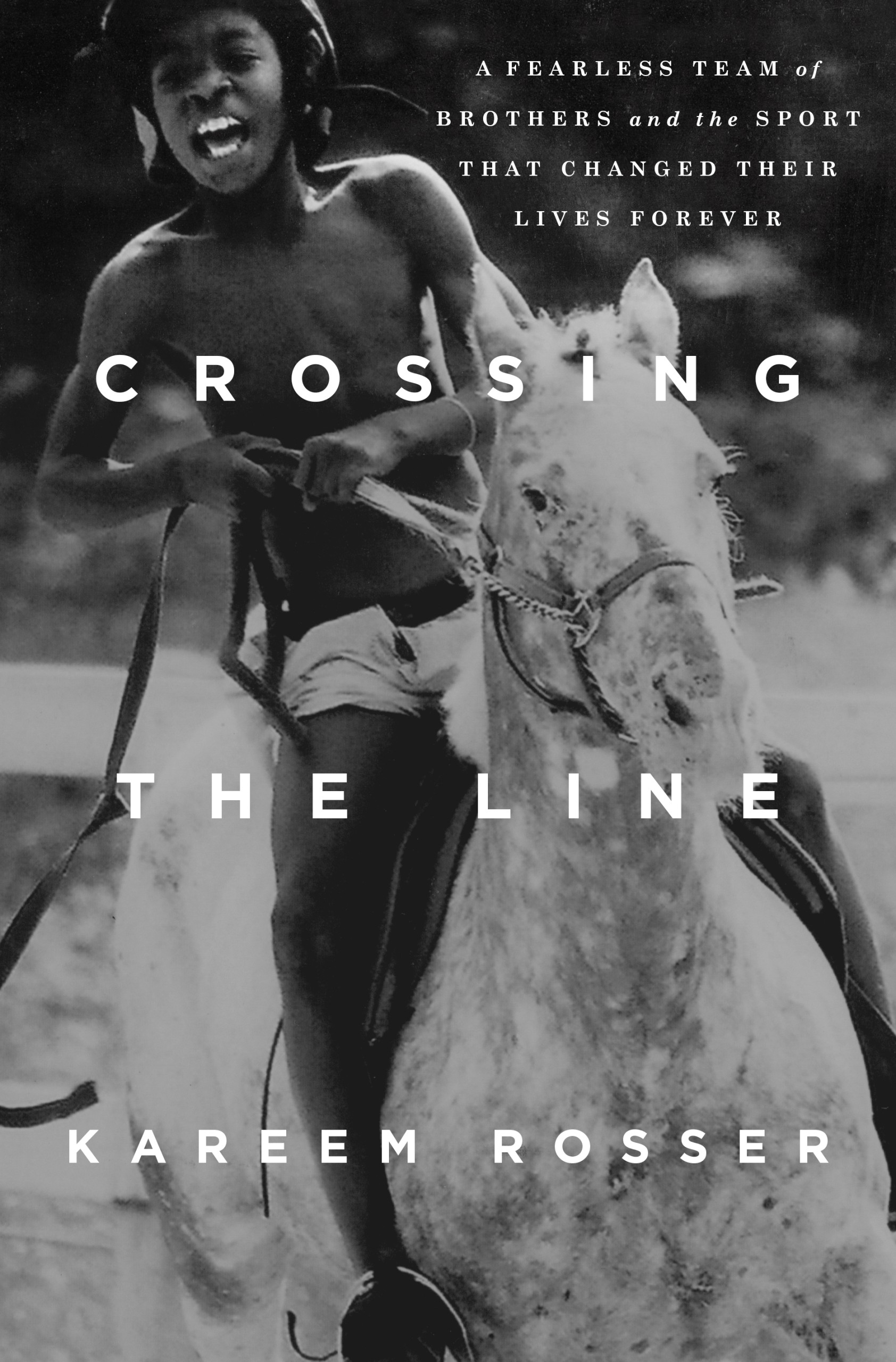

“Crossing the Line: A Fearless Team of Brothers and the Sport That Changed Their Lives Forever” (St. Martin’s Press, 2021) is Rosser’s honest, gritty backstory. The title has multiple meanings, Rosser says, including “crossing into this other world that was unfamiliar, coming from ‘The Bottom,’ and crossing over into all this wealth and different culture.” But the title is also a nod to the sport he loves. In polo, there’s an invisible line, created by an opponent’s right of way, that you may not cross.

The woman who introduced horses into his life—teaching him not only the rules of polo but life-changing rules as well—is Lezlie Hiner, founder of the Philadelphia nonprofit Work to Ride. Rosser and his brothers were drawn like magnets to her Fairmount Park stables by the power of horses.

A stable foundation

Horses were like therapy for Rosser, he says, “considering the trauma and stuff I dealt with as a kid.” That’s why he’s donating 50% of his book’s proceeds to Work to Ride, where today he mentors, coaches and serves as the organization’s treasurer while working as a financial analyst in the city. And Hiner couldn’t be prouder.

“I’m very proud of the fact that he was able to put those thoughts and feelings onto paper—writing a book is a Herculean task,” says Hiner. She founded Work to Ride nearly 30 years ago.

In the process of taking kids under her wings, she has become “like a second mother,” Rosser writes in his book.

“Kids are here anywhere from 10 to 40 hours a week, so it becomes a lifeline, bringing them into a community of their own, like an extended family,” says Hiner.

While the program instills responsibility and hard work—through cleaning the stables, caring for and feeding the horses—Hiner ensures kids’ basic needs are fed too. It’s a mixture of motherly care and tough love.

“We spend a lot of our budget on nutrition, like a school lunch program,” Hiner says. “And we’re providing structure—incentives and discipline when needed—because a lot of the kids are missing those things at home.”

Trailblazers

What would Hiner say to other adults who have the opportunity to mold young lives through similar mentorship roles?

“Letting kids know that they have a support system is very important,” says Hiner, who notes that after-school programs are pivotal. Hundreds of kids have come through Work to Ride over the years.

What was it about Kareem Rosser that propelled him to break barriers?

“He’s just a good person, and he’s also smart enough to not be influenced by negative peer pressure—that’s one of his biggest attributes,” Hiner says. “Growing up, he didn’t buy into that, and that’s what we try to stress with all of our kids.”

There’s a saying “if wishes were horses.” It basically means that life would be easy if all we had to do was make a wish to achieve our goals.

In Rosser’s case, horses really were involved—along with hard work.

At the end of the first chapter of “Crossing the Line,” Rosser reflects on how, as a little boy, he wished for his family’s life to be different and wondered how they were going to escape the cycle of poverty and danger surrounding them.

Today, through his book, he wants others to know that their wishes, like his, can come true.

“I think half the battle is believing in yourself, then the other half is having a few good people in your life to help you get over the hump,” Rosser says. “I think it’s finding that resilient side of yourself and continuing to believe no matter whatever uphill battle you’re facing. The optimistic side of myself has allowed me to go places.”

“Crossing the Line” is available at Philadelphia bookstores or via Amazon. It’s recommended for readers ages 21 and older.